Discover more from Fr. Joe’s Newsletter - Moving to Russia

Groundbreaking New Russian Film about Orthodox Christianity and a Monastery - a Review of 'Holy Archipelago'

On the same level as ‘Man of God’ (St. Nektarios), or ‘Ostrov’. A breathtaking window into the unexpected Christianity rising in Russia, with a powerful message for the world.

A note from Fr. Joe: - I recently watched this and it really is extraordinary. It surprised even me, and I found myself marveling that a film of this level could be funded and made. It made me very glad and thankful, a must-see.

This excellent review was written by an American friend who lives here, not far from me. It is full of insight into how Orthodox Christianity is developing here in Russia. I highly recommend taking the time to read this. It is fascinating.

By an American Christian living in Russia

In these days of war and foreboding about where the world is heading, everyone is in need of some good news. Unexpectedly, a new 1.5 hour documentary film about a major monastery in Russia gives us just that.

I’m not a movie critic, but I would go so far as to say that this is a very great film, great in its conception, the message it delivers, the timing of that message, its technical mastery and beauty, and what it suggests about the future, not just of Russia, but the whole world.

I was deeply moved by Holy Archipelago, which profiles the Solovetsky Monastery, ‘Solovki’ for short in Russian parlance. Afterwards, when trying to articulate why, I struggled for a while, until I realized it was because the message for me was: ‘If these are the kind of people and ideas which are on the rise in Russia, then prospects for humanity are much more hopeful than might otherwise appear.’ By ‘people’, I mean the director, Sergei Debizhev (more about him below), but also the bureaucrats at the Ministry of Culture who funded it, the monks and laymen who speak in it, the celebrity musician (Butusov) who composed the excellent score (more about this below), the applauding critics and cultural elites, the festivals bestowing awards, and, most of all, the Russian audiences viewing it with apparently substantial enthusiasm.

Interestingly, there is substantial demand for this film in markets throughout the global south, in China, in India, the Middle East, and Latin America, and distribution deals are currently being negotiated. Unfortunately due to political sanctions, there are no plans to distribute it in the US and Europe.

It seems to me that this film might be even more important for international viewers, especially American audiences, than for Russian. Reportedly, it will be released with English captions for Western audiences later this year. Its producers have created a good English language website about the film. The production company, 2 Captains, also has a YouTube channel with a playlist of videos related to this film captioned into English. The videos were captioned by ‘Candlestick’ a global volunteer group which adds English captions to Orthodox Christian videos from Russia. Here is their YouTube channel and their Telegram channel.

Holy Archipelago was the hands-down winner in the documentary category at the last Moscow International Film Festival (2022). For decades this festival has been one of the most important in the world going back to Soviet times, due to the historically high level of Soviet and now Russian film making, producing many Academy Award nominations and wins over the years. In normal times, a film winning the documentary category in Moscow would be an automatic nomination at the Academy Awards. Here is a video of him and his wife, producer Natalia Debizheva, accepting their award, and what he has to say is interesting (more about that below).

On one level, the film is a profile of the Solovetsky Monastery, which both Christian and non-Christian audiences in the West will find fascinating, but on another level, it is a window into Christianity as it is being manifested in Russia, and what the film tells us about this Russian renaissance is perhaps more important.

So let me try to describe it.

One’s first impression is that of a very beautiful National Geographic nature film. I watched it on a near IMAX level theater in Moscow and one can see immediately that the film, shot in 6K, was made with the intention of a full cinematic experience, substantially lessened when watching it again on a computer, or even a large flat screen TV.

Arresting and technically perfect time-lapses inside and outside the monastery depict sunrises and sunsets, tides ebbing and flowing, monks harvesting hay reminiscent of the Amish, or dunking crucifixes into an ice hole cut in a frozen lake, along with a lot of dramatic drone footage of those wonderful Russian cupolas and the stunning arctic nature around them. One is tempted to think, “Well, this is all very pretty,” and conclude that this is all it is. The film is so masterful in its technical beauty that one might not notice the far more important message conveyed in the words of the monks, laymen, and the director, via the narrator, interspersed throughout.

I was lucky to have visited Solovki years ago, and it is very much as it is portrayed in the film. I was struck at the time with a feeling of pureness and cleanliness, if that is the right word. It is so far off the beaten track, as if on the edge of the world, it seemed by its very essence to be close to God, far from the fallen world.

Holy Archipelago consists of almost postcard-like tableaux of physical beauty and daily life — forests, ice-floes, schools of white beluga whales cavorting in the arctic sea, and monks baking communion bread, haying, making candles, performing rites outside in bone-cracking freezing cold, and praying indoors with startling medieval, mystical intensity. Interspersed throughout are very short excerpts of interviews with monks and laymen working at the monastery. They explain their beliefs, the role of the church and monasteries, of monks, of the state of our world, and where humanity is heading, with the narrator, representing the views of Debizhev, layered over it all.

I had trouble grasping the import of these spiritual and historic messages, partly because the artistry of the images on the screen were so arresting that I had trouble focusing on the words being spoken. Also, when watching a film in a theater, one can’t pause it and ponder the meaning, as one is wont to do when contemplating profundities. Thankfully, the creators of the film later gave me a transcript of the audio, so let me share briefly, without giving too much away, what was said.

These missives, like little telegraphic messages filtering through the imagery, are brief, but very meaningful. It is a testimony to Debizhev’s own spiritual maturity, that he was able to select a few key ideas, and distill them into a meaningful narrative. He obviously must have had much more footage, but kept things minimal. In an Orthodox Christian sense, it seems apparent that the director himself is ‘spiritually advanced’, if one dare to use such a term. I realized this later, when watching interviews (embedded below) which he gave to Russian media.

Here is some footage of the monks. (not captioned).

As an example, here is the first, brief message, from the abbot of the monastery, Bishop Porfiry, a very well-known and popular personality in the Russian church. Below, I explain why Russians know and like him.

In under two minutes, Debizhev, via Porfiry, brings us this:

A man should always stand before God, in other words, God should always be in his mind and heart, he should always be aware that He exists, and he should always be cognizant of this, even when focused on other tasks.

And there is nothing more beautiful and perfect in the world than a man living this way — a man with a kind, virtuous, moral, selfless soul, a man willing to sacrifice for others, a man emitting a glow of holiness, a man understanding the most important thing - that there is a Creator.

The Church’s real activity is to keep this lamp lit. Its main task is to keep men focused on God, so that they are always standing before Him.

Men were given rational minds by God for one reason only, to be in communication with Him. Monks and monasteries replicate that function. We monks dedicate our lives to this - to keep this lamp lit, to reflect this in our hearts and our deeds.

How this light will affect the world - whether it lights up the heart of one man, or of many, that is up to God, not to us.

Dedicate your works to God, and God will take care of the rest.

The film continues in this vein, with arresting and mesmerizing images of Solovki, the life of the monks and laymen, and the glorious nature in which they live, sprinkled with pearls of spiritual wisdom from those interviewed.

The abbot and the monks speak slowly and concisely. One sees them carefully choosing their words to capture the right spiritual meaning and nuance, to which the gloriously flexible and subtle Russian language, so friendly to poets, is so well suited. It is a sign of men experienced in discussing spiritual concepts among themselves, and experienced in seeking to share them with others.

Debizhev’s team, which is based in St. Petersburg, visited the monastery dozens of times over 2 years, seeking to capture the changing seasons and various striking rites performed at different times of year. In one of the interviews, Debizhev explains that after a few visits, the monks and the abbot realized that this was no typical film, that the team was trying to achieve something important and extraordinary, and gave them greater access than would otherwise be the case.

One example of this is that they allowed them to film a rite of tonsure, the ceremony in which a novice becomes a monk. This level of access is an almost unheard of rarity, as the rite’s solemnity and gravity could well be distorted by the presence of cameramen. It appears, appropriately, as the last vignette, and is masterfully rendered.

All of the personalities presented are compelling, but perhaps my favorite is George, the man in charge of the woodshop. Judging from the footage, some of the woodshop’s main products are massive wooden crosses, engraved with Christian symbolism, which are then erected around the archipelago. Prior to the revolution there were, astoundingly, over 3000 such crosses around the monastery.

In Russia, the word for such a cross is ‘Poklonnii Krest’, and there is no good English equivalent. ‘Memorial cross’ gives an approximation, but doesn’t really capture it, and it is sometimes translated as ‘crosses of worship.’ A literal translation would be something like: ‘an outdoor cross intended for worshiping, bowing, and praying’. Essentially, the idea is that one puts these up in the outdoors — they can be in parks, suburbs, on lawns of churches or other buildings, or in remote nature — and Christians pray around them, alone or in groups, often performing prayer services.

George treats us with a sermon worthy of a sage on the meaning of the symbol of the cross, the proper relation between body and spirit, how ego has replaced God in the modern world, and much more. One can imagine him laboring in the woodshop pondering these ideas, and only marvel at the serenity and idyllic satisfaction of such a life. Here is some of that footage from a trailer for Debizhev’s next film, The Cross (with captions), which I describe in more detail below.

And here is another trailer for The Cross with footage from around the world. It looks excellent:

In preparation for this review I ended up watching the film 3 times, once in a near IMAX quality theater in Moscow, once at home on a good-size TV, and once on my laptop, and it became clear to me, and the director has also explained this in interviews, that the film was very much made to be seen on a big screen with good quality audio, and takes full advantage of these possibilities. It is great on any screen, but the bigger, the better.

Another interesting thing, to me, it was as interesting to watch the 2nd and 3rd time, as the first, which is unusual. For me, the reason was that the film’s imagery is so meticulously crafted that with each subsequent viewing one notices more and more deliberate small details and techniques, and one begins to appreciate how much thought and effort went into every detail: the sequence of the themes raised, how well-composed and appropriate the music is, the sound engineering, again - the import of what the monks are saying, and what a polished accomplishment this is. It comes together in a very harmonious and felicitous way, leading one to wonder if spiritual forces have had some role in how the film came out. Like all good spiritual content, the more you return to it, the deeper it gets, and this is very unusual in film.

Why this film matters for Western Christians and those curious about Russia

People in the Christian West, but also around the world, know very little about the details and character of this renaissance of Christianity in Russia we keep hearing about. Holy Archipelago is a window into that world, and it reveals that the Christianity being revived differs greatly from its Western cousins to the extent it is anchored in historical tradition rather than seeking to adapt the faith to modernity.

The Russian Church in its entirety, and by that I mean the leadership, the Bishops, the priests, and the faithful, are practicing authentic Christianity as it was practiced before the revolution, which itself clung to the ancient form of Christianity that predated the east/west schism that had occurred centuries before. This is extraordinary, and of primary importance mostly misunderstood by Christians outside of Russia.

If one listens closely to the bits of spiritual wisdom in the words of the monks, a theme emerges: for centuries the world has been moving away from God, and this is the reason for the ever increasing catastrophes visited on humanity, as the monks understand so well due to Russia’s excruciating suffering at the hands of their atheist tormentors in the 20th century.

Towards the end of the film, the monk Sebastian relates the idea, widely held among Russian Christians, and prophesied by Russian saints and elders (monks who have achieved a very advanced level of spiritual enlightenment), that Russia will emerge as a bastion of Christian freedom in a world otherwise completely under the control of Antichrist, that Christianity will never be defeated there, and in fact will grow stronger as the rest of the world succumbs, and that Russia will be an ark of salvation to which Christians from around the world will migrate. Here are some more of these prophecies.

(For more memes with similar prophecies, visit Global Orthodox on social media - Twitter, Telegram, Gab, Instagram, and Facebook.)

Indeed, this tradition of holy elders is but one of many examples of how the ancient faith being revived in Russia is fundamentally different from how Protestant and Catholic Christianity is evolving. Here is an article which describes this phenomenon, which apparently is alive and well in Russia.

Another example of this return to ancient tradition is the very existence, and crucial role, of monasteries themselves. Protestants canceled them in the 16th century because they were never mentioned in the Bible, and were seen as seedbeds of church corruption and worldliness (which was a fair accusation at that time in western Europe). Catholics still have them, but they have dwindled and become anemic, along with most of the Catholic church, save for the remnant “trad” movement.

Here Russia, again, has taken a different path. Russia had a very vibrant monastic tradition up until the revolution, and it actually flowered in the 2nd half of the 19th century, and into the 20th, coinciding with the extraordinary renaissance (the Silver Age) of Russian literature and art in general, birthing a brilliant crop of saints and elders. At the time of the revolution, Russia had over 800 monasteries, which is an enormous number, many of them flourishing.

What is extraordinary is that with the fall of communism, almost all of them were returned to the church. Many of these are very substantial physical structures, often medieval forts, often with substantial buildings and infrastructure. These monasteries are gradually coming back to life, and Solovki is an outstanding example. Here is an interactive map of them, maintained by the official Russian church.

In the Orthodox tradition, long gone in the West, monasteries play a crucial role in the spiritual life of a nation. In them, monks, undistracted by worldly cares, in extreme discipline, asceticism, fasting, and prayer have the possibility of achieving a level of spiritual enlightenment which would be much more difficult (but not impossible) to reach in secular society. They then strengthen the overall spiritual level of the nation through their prayers, their teaching, and their example.

Holy Archipelago gives us a window into this extraordinary world. In effect we are peering into a furnace of Christian intensity, a world of men immersed in the spiritual teachings handed down over 19 centuries by the saints, a world of spiritual warriors engaged in ‘spiritual warfare’, as they term it, doing battle for the salvation of humanity. How appropriate that this often takes place inside the walls of actual forts, built centuries ago to fight off marauding Islamic hordes and Polish and German Catholics sent by the Papacy to destroy Orthodoxy.

And this, it seems to me, is Mr. Debizhev’s great achievement, making this film very much more than a pretty picture show. He is deeply enough immersed in the Christian life in Russia, as one can see from his interviews (below) to understand the role these monasteries play, to choose precisely this monastery, and this particular abbot (see below) and then to select the right short quotes of those interviewed which efficiently illustrate the profound spiritual wisdom flowing from these fonts of traditional Christianity, rooted in the teachings of the saints.

Some history of Solovki

Despite its enormous distance from the great cities of Russia, Solovki has a rich history intertwined with Russia’s own. Founded in the early-15th century, it became an important citadel, a center of economic, political, and military power for the growing Russian state. It played important roles in various wars against Sweden, and even in the Crimean war of 1851. Massive stone walls 4-6 meters thick, with towers as fortifications were built in the late-16th century. Wikipedia has a reasonably good account of this history.

The walls themselves are something of a mystery, because their lower levels consist of enormous, multi-ton boulders, many of them as big as a good-sized SUV. One can see them clearly in the film. The mind struggles to imagine how the medieval builders lifted and moved them, especially given the icy climate.

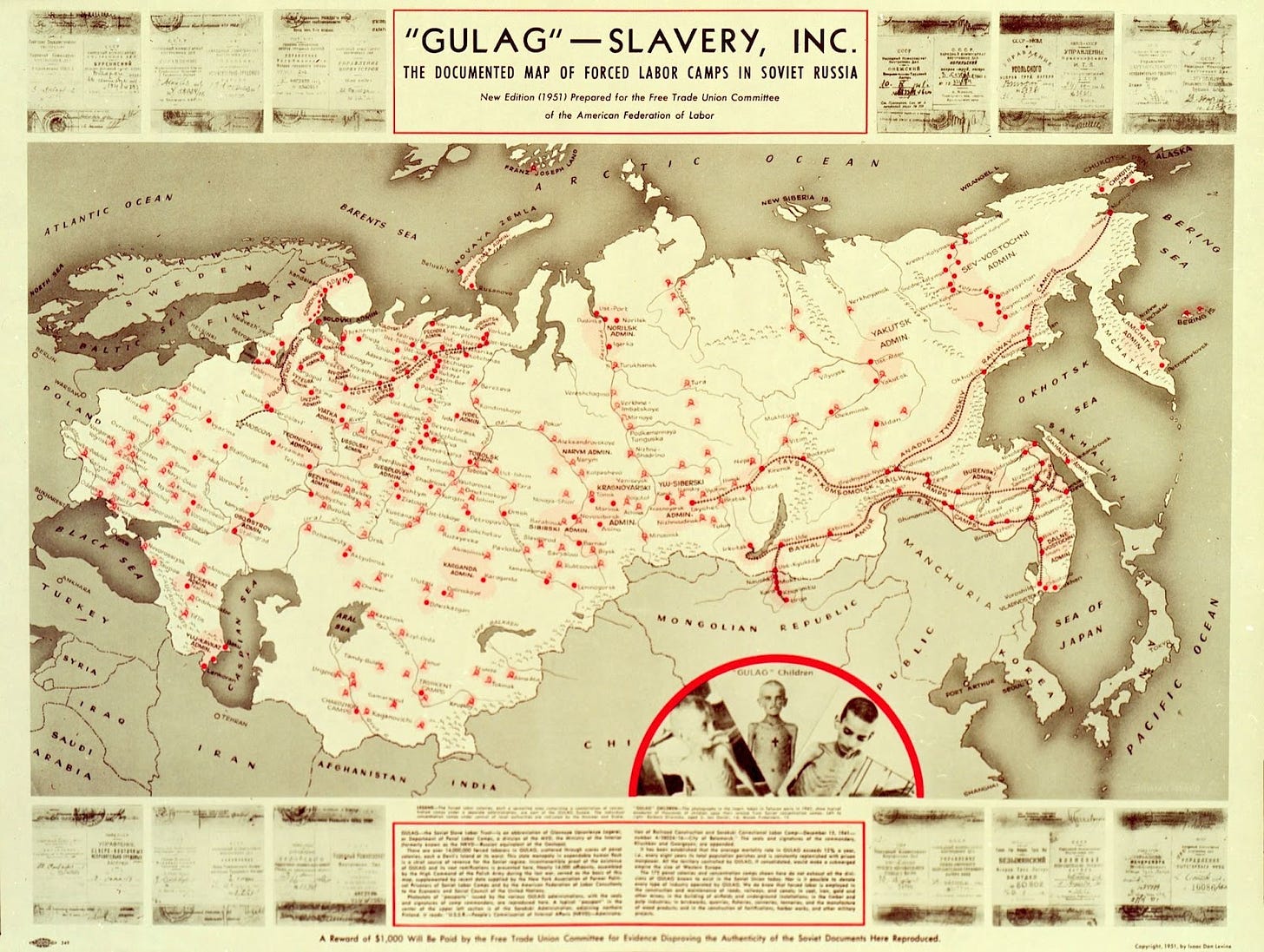

However it was in the tragic Bolshevik period that the monastery took on a historic and spiritual role of almost cosmic significance. The monastery was turned into a labor camp and prison in the early 20s, part of the notorious network of labor / death camps of the Russian north. After the civil war, the Bolsheviks launched massive industrial infrastructure projects, breathtaking in their audacity and cost, the most important being the140 mile long White Sea Canal, linking the arctic White Sea, where the Solovetsky monastery is situated on an island, with Lake Onega, 500 miles northwest of St. Petersburg. These massive projects served two goals: the extermination of political enemies, and the construction of infrastructure and industry which would be impossible without colossal suffering, disease, and sacrifice of human life. It is estimated that 25,000 lost their lives building the White Sea Canal, with the health of countless more shattered.

Solovki, being on an island, was more of a prison and death camp, and for whatever perverse logic, many writers and literary figures were sent there to die. The cruelty and savagery of the killing was unprecedented in human history. The previous persecutions of Christians under the Romans, and during the European religious wars, pale in comparison, both in quantity and brutality. A favorite implement of torture was simply the cold weather - forcing men to live in the cold, essentially freezing them to death. Symbolically, a 19th century church built on a hill not far from the main monastery was used as an execution zone, complete with massive pits to accommodate the piles of cadavers. Many of the victims were priests and monks, choosing death over renunciation of their faith.

This painful history is so well-known to Russian audiences, and has been so much talked about since the fall of the USSR, that there was no need for Debizhev to dwell on this tragic episode, and it is covered in a 10 minute segment in the middle of the film, narrated at times by the kind voice of the monk Sebastian, explaining that Russia was crucified for the sins of the world, humiliated and mocked with unimaginable cruelty, only to resurrect as a Christian light to the world. Sebastian explains:

What people lived through here, is like a fertilizer of the soil, out of which grows a new holiness. We believe this with all of our heart.

So the monastery is a living symbol of Russia’s extraordinary role today, a country which endured unimaginable torments during the 20th century, renewed by the blood of those martyrs, purified by the mystical power of suffering and sacrifice, including the ultimate sacrifice on a scale unparalleled in history. Solovki’s testimony explains in real terms that Russia is an historic power emerging from the great trauma visited upon it by atheism, rejecting the West’s seemingly inexorable march into the same abyss.

It requires skill and a sure hand to give these horrific events — of such recent memory — their due place, without overshadowing the film with a kind of gruesome pallor, and the director navigates this ground successfully.

Indeed, the mood of the film is in stark contrast to this unsettling tangent. The film highlights the beauty of God’s creation, and the harmonious way the monks’ lives and state of mind fit in. The monastery has a rather comprehensive photo section on its website which gives a sense of what life is like there.

About the director and the composer of the score

The person of director Sergei Debizhev, Russia’s most prominent documentary film maker (Wikipedia), is another aspect I found fascinating. Not professionally schooled as a director, he claims that he doesn’t think of himself as one, and that neither do other Russian directors, who he says often resent the innovations he has introduced into the genre.

Russian, born in the mountain region of the North Caucasus, he trained as an artist in St. Petersburg, and got his start making music videos in the thriving Russian rock scene of the 90s, as a friend and colleague of Russian legends such as Boris Grebenshikov, Victor Tsoi, and hearthrob Vyacheslav Butusov. Butusov composed the music for Holy Archipelago, setting many a woman’s heart aflutter across Russia, and he himself is a major popular draw for the film. Here is Butusov in a promotional video for the film:

And here is the message this lion of Russian rock, against a background of holy icons, chose to share, so different from the demonic drivel of Western rock ‘icons’:

Dear friends, I, together with the team who made this film, are with you in spirit. I watch this film with great joy.

In these times, we are bombarded with endless news of disease, military conflict, and natural disasters. In order to replenish the strength of our souls, we need a certain kind of support. Solovetsky monastery is such an unusual, wonderous place. Looking at these enormous boulders and the centuries-old fortress walls, you begin to understand the power of spiritual strength.

In Solovki, we understand why Russia is again an ark of salvation.

And here again, we are confronted with this striking contrast of directions in which top Russian cultural personalities are moving vs. their Western counterparts.

Butusov has produced an excellent score, reflecting his spiritual depth and just perhaps, an understanding of Orthodox Christianity. Incidentally, Russian rock, appropriately for this land of poets, differs from its Western inspiration in that the words, and their spiritual (though usually not Christian) depth, are considered more important than the melodies. Russian rock classics are more poems set to music, which can often strike a Westerner as melodically pedestrian, rather than melodies with lyrics as an afterthought. Russians love the songs for the words, not the music, and rhapsodize about how ‘soulful’ they are, often leaving a Western listener slightly baffled, to which a Russian friend inevitably shakes their head and smiles in condescending sympathy: ‘You have to be Russian to understand’. Bob Dylan ballads are a Western analog.

Debizhev, 65, who runs his production company with his wife Natalia in St. Petersburg, evolved from a rock-loving hedonist into a deeply conservative Christian, indeed, a monarchist, and an admirer of the ideas of the political philosopher Alexander Dugin. This comes back to the beginning of this review — who are this new wave of Russian cultural thought leaders? How are they different from their Western colleagues? Debizhev is not unusual in his faith among a new breed of Russian celebrities, journalists, and politicians, and their role and prominence has significantly increased since the beginning of the Ukraine war, as their colleagues who aped the soulless, nihilist, atheist depravity of Hollywood fled the country en masse. Here is an interesting report on some of the more prominent ones, suggesting this is no minor phenomenon.

His two previous films which established him as the uncontested leader of Russian documentary films, perhaps a rough equivalent of America’s Ken Burns (but much more interesting in my opinion), were a biopic of Ivan Solonevich, a leading refugee opponent of the USSR, a monarchist despised and hunted by Stalin’s NKVD around the world, and a history of the Russian revolution, both made for the St. Petersburg studio Lendok, and both financed by the Russian Ministry of Culture. You can find them on YouTube: The Last Knight of the Empire (2014), and Red Hot Chaos (2017). Here are the trailers (in Russian):

In these films we can see Debizhev’s ever more innovative techniques, evidently thinking outside of the constraints which might limit more traditionally trained filmmakers.

And here is the trailer to a loving homage to St. Petersburg, ‘Hymn to the Great City’ (2015, IMBb), which is on YouTube in its entirety here:

During the release of Holy Archipelago this Spring, I found these two interviews of him (with English captions) fascinating, because it gives an insight into his faith and shows him to be a deeply thoughtful and unusually articulate artist. They include more remarkable footage from the film.

And here again is the video of him and his wife, producer Natlia Debizheva, accepting their award at the 2022 Moscow Film festival.

Mr. Debizhev’s words to Russia’s mostly liberal, worshiping-all-things-Western beau monde at the festival are indicative of the changes working their way through Russian society:

I think it's long past time to move on to the bright side of being. We should stop scaring audiences, stop tickling and titillating them. It's time to turn directly to their soul. We will make every effort to do this.

As Aristotle said, the purpose of art is catharsis. It seems to me that a person deserves to be directed to the light-giving side of life. Criticizing the vices of society is important, but still, the goal of real art, it seems to me, is different.

In another interview, he was asked why he believes monarchy as a form of government is superior to democracy. Without skipping a beat, he replied that the process by which a monarch is trained and selected for the job, and the Christian goals and values he has, makes it much less likely that an incompetent scoundrel would be running the country than if it were an elected president, a reasonable view it seems to me, reviewing our past history, but especially our current crop of mediocrities across the Western world.

Indeed, monarchism is a mainstream political position in Russia, especially among Christians, and taken entirely seriously as a valid and realistic outcome even by non-monarchists, something most Westerners would find surprising. Again, here is an example of this ancient Christianity, so different from that in the West, making rather unexpected changes to public life. Pre-revolutionary ‘monarchical theology’, going back to the Byzantines, stipulates that a country is not fully Christian, and will not be fully blessed by God, unless ruled autocratically by a Christian monarch, with the Patriarch and the church subordinate to him. His source of political power is not ‘the people’ — as in Western democracies, and indeed, as in the current Russian constitution — rather, God.

Reinforcing this are the teachings and prophecies of major and influential Russian elders and saints that Russia will return to precisely this form of government, not the fake and ridiculous constitutional monarchies which still survive in Europe as tourist attractions, but the real thing. Some of the greatest Russian and Greek contemporary saints and elders of the 20th century predict this, such as St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, elder Nikolai Guryanov, and many others.

The film doesn’t address this question of monarchism, but I allow this short digression because the director holds to these views, as do many other influential Russians, and in order to illustrate that the film is a window to this very different world taking shape in Russia.

Debizhev is currently working on another Christian documentary, to be released at the end of 2024, which seeks to explain the meaning of the symbol of the cross. There is a section of Holy Archipelago which addresses this topic, and perhaps during shooting he realized that this subject alone was worthy of an entire film. His team is currently traveling around the Christian world - The Holy Land, Ethiopia, Egypt, Georgia, and of course Russia, filming footage. Here is are two trailers for that film, using some of the footage from Holy Archipelago. It looks like it will be as good as Holy Archipelago, perhaps better.

Indeed, Russia is experiencing a renaissance of Christian and traditional values film-making. The Russian union of cinematographers recently started a Telegram channel (in Russian) which reports on events in that space.

About the abbot

A few words are in order about the personality of the abbot of the monastery, Porfiry, because he emerged as a popular Russian figure during the covid episode, which gripped Russia as much as anywhere else.

In many respects, the Russian Church — unlike, for example, the Georgian (country) — showed itself unable to understand the political or spiritual import of what was occurring, with its leadership outdoing each other in shutting churches altogether, demanding everyone to mask-up, lock-down, and get the mystery jab, which in Russia was essentially a licensing of the same MRNA clot shots coming from Western Big Pharma. Priests busied themselves disinfecting communion spoons and spouting WEF inspired theology. In this, the Church was deeply out of step with the views of most believers, indeed, of most of the country, where sentiment was overwhelmingly against vaccinations, and the government had to resort to coercive measures.

When all was said and done, 70% of Russians did not take the vaccine, but the resistance was stiffest among strong believers, who, it appears, intuitively understood that the vaccines were dangerous, and being pushed by a distinctly anti-Christian faction in the Russian elites. No doubt the saints themselves, of whom Russia has more than any other country due to the horrors of the Soviet terror, were interceding.

Among Russian bishops, Porfiry, 58 years old and a trained scientist in the field of aviation, was one of very few who, right from the start, urged his country and flock not to fall for the delusion. The monastery has a YouTube channel which broadcasts services, and separately, Porfiry’s short but powerful sermons, which are the apogee of what Orthodox Christian sermons should be, solidly grounded in the teachings of the Holy Fathers. Week after week, he sought to warn Russia about the dangers of lockdowns and mandatory vaccination. He was eloquent, erudite, and wise, earning the love and respect of millions of Russian faithful. Here is an example of such a sermon with English captions:

Porfiry has also stood out among Russian bishops in his outspoken support since 2014 for the Donbas republics in their struggle with Kiev, framing the conflict in spiritual terms as one between Christian and anti-Christian forces. In this instance, again, he pre-empted the mainstream Russian church, which has only recently come out in strong support for Russia’s war effort in the Ukraine over the last year. Prior to that, for the first 6 months of the current conflict, and certainly back in 2014 when war first erupted, the church was lukewarm, tentative, and accommodationist, worried about an open conflict with her sister church in Ukraine.

Conclusion

Holy Archipelago has been an unusual commercial success in the Russia. Showered with awards from 12 Russian (and one Serbian) festivals, and with more imminent from around the world, it was shut out of most major Western ones. It is now again applying to those, and hopefully some of these will reconsider this important film, having overcome their ‘latest thing’ and ‘I support Ukraine’ hysteria. In case representatives from these festivals are reading this article, here is the profile of the film on Film Freeway (accessible only by festivals).

Holy Archipelago was widely promoted in Russia in mainstream media and is currently playing in Russian theaters in over 500 towns and cities, to applause from audiences and critics. This speaks to a cultural tectonic shift underway in Russia, as cultural elites move away from Hollywood-inspired sexual depravity, cynicism, atheistic nihilism, and violence to a culture which inspires and uplifts and poses important questions appealing to man’s higher calling.

The budget of the film was about $200,000, which may not sound like a lot, but adjusted for purchasing parity in rubles, it would be the equivalent of perhaps $1-2 million if such a film were shot in the US. Released in Russian cinemas in the beginning of March, it has grossed about $250,000 (again, adjust for purchasing parity) within 2.5 months, unprecedented for documentary films in Russia, which almost never make it into commercial theaters at all. It is scheduled to run in cinemas here until the end of August, after which it will be available (in Russian) on Russian streaming platforms, for years afterwards. Debizhev’s production company is currently in negotiations to release the film in theaters and on streaming platforms in major foreign markets such as China, the Middle East, and India, where there is growing demand for high quality Russian cinema.

Sadly, the main American and European distribution channels are closed to Russia due to political and military conflict and related sanctions, and Debizhev is currently looking at making the film available to audiences in these markets via crowdfunding.

It is a shame that Holy Archipelago cannot simply be put on the internet for free, for it speaks precisely to what the world needs to hear. Such is the contradiction of commercial film distribution - many great films, due to their merits, are walled off behind paid platforms, greatly restricting their reach.

I very much hope this film will at least find its way onto major streaming platforms like Amazon or Netflix, moral cesspools that they are, so that as many people as possible can see it, and eventually onto free access on public video platforms.

If you understand Russian, or if the film gets to Western audiences, go see it. You’ll be glad you did.

Unfortunately this film is not available in India!

Amazing article - covering so much.

I will surely came back and read it again, and also look deeper into Mr. Debizhev’s work!